Athens: The Cradle of Democracy, Drama and Doctrines

Athens, a city steeped in history and mythology, stands witnessing the human ingenuity and the enduring allure of ancient civilisations. Nestled in the heart of Greece, this iconic metropolis has, for millennia, been a beacon of culture, philosophy, and democratic ideals. The city’s story is not just a chapter in a history book; it is a sprawling epic spanning ages, from the dawn of Western civilisation to the complexities of the modern era. The origins of Athens are shrouded in the mists of legend, said to have been founded by Cecrops, half man and half serpent, and named after Athena, the goddess of wisdom, as she won the city’s patronage by bestowing upon its people the gift of the olive tree as per the myth. This blend of myth and history is a recurring theme in the Athenian narrative, where the line between reality and legend often blurs, giving the city an almost mystical quality.

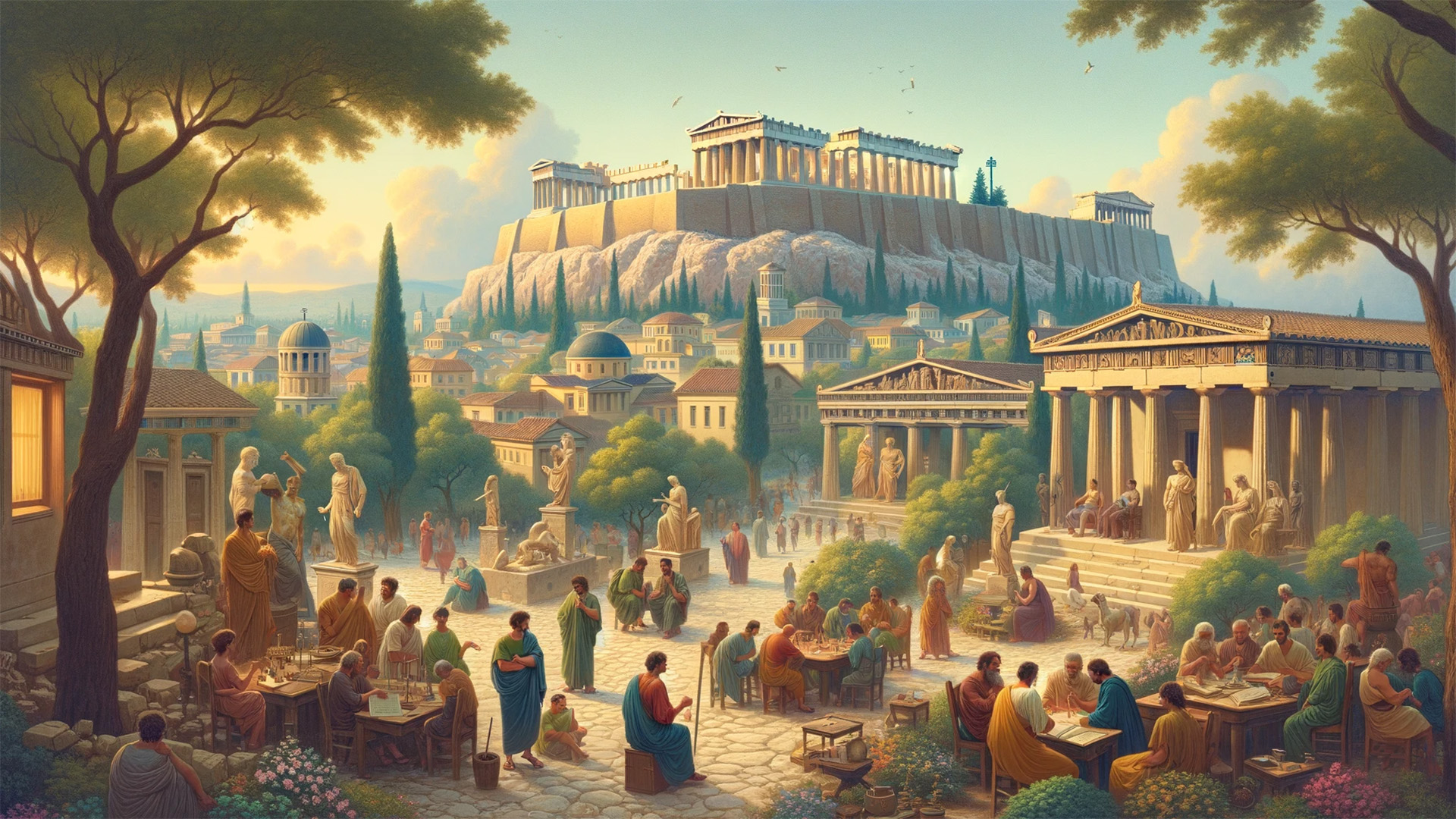

As you walk the streets of modern Athens, the whispers of the past are ever-present. The city’s architecture is a palimpsest of its varied history, with ancient ruins like the majestic Parthenon, a symbol of classical Greek civilisation, coexisting with Byzantine churches and neoclassical buildings. This juxtaposition of old and new is emblematic of Athens – a city where history is not confined to the past but is a living, breathing part of its present. However, the most enduring legacy of the ancient city is its intellectual and cultural contributions to the world. It was here that democracy was born in the 5th century BCE, a revolutionary idea that reshaped the Western political landscape. The city was a nexus for philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, whose thoughts and teachings still resonate today. Moreover, Athens was a crucible for the arts, from the tragedies of Sophocles and Euripides to the timeless sculptures that epitomise the ideals of human form and beauty.

Yet, to truly understand Athens, one must look beyond its monuments and ruins. The city’s soul is in its people – resilient, proud, and deeply connected to their rich heritage. From the lively tavernas in Plaka to the bustling markets of Monastiraki, Athens is a city alive with the vibrancy of daily life, where history and modernity coalesce into uniquely Hellenic shades. In Athens, the past is not a bygone era; it’s a legacy that continues to shape the city’s identity and charm.

City of Violet Crown: Emergence & Reformation

Around 1250 BCE, Athens emerged from the shadows of history into a distinctive entity, yet its narrative was still deeply intertwined with the broader spectres of Mycenaean civilisation. This era, often shrouded in the mystique of legends and epic tales, was when Athens was not yet the luminous beacon of democracy and culture it would become. The city, ensconced in the Attica region, was likely a modest cluster of buildings, more akin to a fortified stronghold than the sprawling metropolis it was destined to be. Life in Athens during this period was fundamentally agrarian, with a societal structure that revolved around tribal and kinship ties, mirroring the hierarchical and palace-centric culture prevalent in Mycenaean Greece.

Fast forward to the mid-7th century BCE, and the landscape of Athens had undergone a transformative shift. The advent of the Archaic period marked a renaissance in Greek civilisation, and Athens was at the forefront of this awakening. This period was characterised by profound socioeconomic changes, spurred by increased interactions with other Mediterranean cultures, leading to the expansion of trade and a subsequent rise in urbanisation and wealth. One of the most significant reforms during this time was establishing a codified legal system. The draconian laws, attributed to the lawmaker Draco in the early 7th century BCE, were a pivotal step towards formal governance, replacing the arbitrary rule of local aristocrats. Although harsh, these laws were a precursor to more equitable legal frameworks and set the stage for the birth of democracy.

In the mid-7th century BCE, Athens was also a hotbed of artistic and architectural innovation. The period saw the genesis of monumental temple architecture and the refinement of pottery and sculpture, laying the groundwork for the artistic triumphs of the Classical era. The evolution of the Greek alphabet, adapted from the Phoenician script, was another milestone of this era, catalysing the proliferation of written literature and preserving history and myth. In essence, the transformation of Athens from 1250 BCE to the mid-7th century BCE was a journey from a relatively obscure Mycenaean settlement to a prospering city-state on the brink of its historical height. This era laid the foundational stones of Athenian identity – a blend of artistic expression, legal reform, and social restructuring – that would shape Western civilisation in time.

Relishing the Golden Times

In the 5th century BCE, Athens, under the stewardship of statesman Pericles, entered an epoch that would later be celebrated as its Golden Age, an era marked by unprecedented advancements in art, philosophy, and governance. Following the onset of the Peloponnesian War, this period saw Athens at the zenith of its power, epitomising the ideals of classical Greece. The city-state, flourishing through the tributes of the Delian League, embarked on an ambitious cultural and architectural magnificence project, making it the epicentre of Greek civilisation. The hallmark of this age was the remarkable flourishing of arts and intellectual thought. Athenian drama reached its pinnacle with playwrights such as Sophocles and Euripides, whose tragedies and comedies not only entertained but also probed the depths of human experience and morality. The era was equally significant for the progression of philosophical thought, led by figures like Socrates, whose methods of inquiry laid the foundations of Western philosophy. This intellectually vibrant atmosphere encouraged and celebrated public discourse and critical thinking, making Athens a beacon of knowledge and wisdom.

Architecturally, the Golden Age witnessed the transformation of the Athenian Acropolis into a bastion of classical beauty and harmony. The construction of the Parthenon in 433 BCE, under the direction of Phidias, stands as a testament to the artistic and engineering prowess of the Athenians. This period was also marked by a surge in sculptural and artistic endeavours, emphasising realism and the human form, reflecting the humanist ethos of the age. However, this period of cultural and artistic prosperity had its complexities. A robust democratic system underpinned the glory of Athens during these years. Yet, it also grappled with the contradictions of maintaining an empire and navigating the tumultuous waters of Peloponnesian politics. The Golden Age, therefore, represents a paradox of Athenian history – a time of unparalleled cultural achievements amidst the backdrop of political strife and conflict. Nonetheless, the legacy of this era left an indelible mark on the annals of history, symbolising the heights of human potential in art, thought, and governance.

Struggles and Survival of Sedulous City

As the 4th century BCE unfolded, Athens, once the unassailable seat of democracy and culture, navigated a dramatically altered geopolitical landscape. The ascendancy of Macedonian power under Philip II and, subsequently, his son, Alexander the Great, marked a seismic shift in the balance of power within the ancient Greek world. The once proud and independent city-state of Athens, along with others, was compelled to reckon with the realities of Macedonian hegemony. This era signified a departure from the glory days of the 5th century BCE, ushering in a period of uncertainty and adaptation.

The Macedonian conquest, while curtailing the political autonomy of Athens, paradoxically did not stifle its cultural and intellectual dynamism. The Hellenistic period, as it came to be known following Alexander’s vast expansion of the Greek world, was a time of remarkable intellectual ferment and cross-cultural exchanges. Athens continued to be a hub of philosophical activity and education, attracting scholars and students from the Hellenistic world. The Lyceum and the Academy, founded by Aristotle and Plato, respectively, thrived during this period, perpetuating the philosophical traditions central to Athenian identity. However, the political landscape of Athens during this era was characterised by a loss of its former democratic ideals and independence. The city witnessed several oscillations in governance, swinging between Macedonian influence and brief periods of relative autonomy. The struggle to maintain its cultural and political identity in the face of external dominance was a defining challenge for Athens during these centuries.

In 86 BCE, the landscape of Athens was dramatically altered by the siege and subsequent capture by Roman General Lucius Cornelius Sulla. This event marked a pivotal moment in Athenian history, symbolising the end of its relative autonomy and the beginning of a long period under Roman dominion. Sulla’s siege was notably brutal, leaving much of the city ravaged and its walls dismantled, a stark reminder of the city’s diminished standing in the Mediterranean world. The aftermath of this conquest saw Athens being reduced to a shadow of its former glory, a provincial town within the vast Roman Empire. Despite this, Athens retained its cultural and intellectual stature, continuing to attract scholars and students, thus maintaining a semblance of its ancient legacy.

Another significant event in Athens under Roman rule was the construction of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, completed in 131 CE under Emperor Hadrian. This monumental temple, dedicated to the king of the Greek gods, Zeus, was one of the largest in ancient Greece, exemplifying the Roman influence on Greek architecture. The temple’s construction, which had started centuries earlier, symbolised the enduring cultural and religious ties between Greece and Rome. Despite the political subjugation, such architectural feats underscored a period of relative peace and prosperity under Roman rule, allowing Athens to continue as a centre of philosophical and artistic activity.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century CE ushered in a new chapter for Athens, as it became part of the Byzantine Empire. This transition marked a significant shift in the city’s cultural and religious landscape, with Christianity gradually superseding the ancient Greek pantheon. During the Byzantine period, Athens experienced a transformation in its architectural and artistic expressions, evidenced by the rise of Christian churches and the repurposing of ancient temples.

By the 10th to 12th centuries CE, Athens, while no longer the political powerhouse of yore, maintained a modest but steady presence in the Byzantine Empire. The city, though eclipsed by the grandeur of Constantinople, continued to be revered as a symbol of ancient Greek heritage. This period saw a blend of classical and medieval influences in the city’s art and architecture, reflecting the layered history of Athens. Despite being far removed from its golden age, Athens, in the medieval era, stood as a living museum of its storied past, bridging the ancient and medieval worlds in the shades of its enduring legacy.

In 1458 CE, a significant chapter in the long history of Athens commenced with its capture by the Ottoman Empire, marking a profound shift in the city’s trajectory. This conquest was part of the larger Ottoman expansion in Southeastern Europe, a period that dramatically reshaped the political and cultural landscape of the region. The fall of Athens to the Ottomans signified the end of Byzantine influence and the beginning of several centuries under Ottoman rule. Under the Ottomans, Athens underwent notable changes, particularly in its architectural and societal structures. The city’s ancient and Byzantine monuments were often repurposed or altered to fit the Ottoman administration’s and culture’s needs, exemplifying the layers of history that define Athens. Despite the decline in its global significance during this period, Athens remained a symbol of ancient Greek civilisation, albeit under the shadow of Ottoman governance, until the Greek War of Independence in the 19th century catalysed its resurgence as a pivotal city in modern Greece.

Greek War of Independence & Re-emergence of Athens

The Greek War of Independence, beginning in 1821, marked a fervent period of struggle against Ottoman rule. This movement, steeped in the desire to recapture the glory and freedom of ancient Greece, eventually led to the establishment of an independent Greek state. Athens, once again, was poised to reclaim its status, not just as a symbolic beacon of classical heritage but as a vibrant, self-governing modern city, echoing the democratic principles and cultural prowess of its illustrious past.

In the contemporary era, Athens has metamorphosed into a resounding, modern metropolis, gracefully blending its illustrious ancient heritage with the dynamism of a 21st-century city. As the capital of Greece, it stands as a symbol of resilience and renewal, having undergone extensive urban development and revitalisation, especially since the late 20th century. The city’s skyline, a mosaic of classical ruins, Byzantine churches, and modern architecture, narrates the interesting tales of its history. Today, Athens is the political, economic, and cultural heart of Greece and a hub of innovation, arts, and education.

Athens is a destination par excellence, attracting millions of visitors annually. Tourists are drawn to its historical charisma, epitomised by the Acropolis, an ancient citadel that houses several historical buildings of great architectural and historic significance, most notably the Parthenon. The city’s museums, including the Acropolis Museum and the National Archaeological Museum, offer an invaluable glimpse into ancient Greek civilisation. Beyond its historical treasures, Athens enchants visitors with its vibrant street life, delectable Mediterranean cuisine, and the warmth of its people. The city serves as a gateway to the Greek islands, making it not just a stopover but a central part of the quintessential Greek experience. With its unique blend of antiquity and modernity, Athens continues to captivate and inspire, holding a special place in the hearts of travellers worldwide.

References:

-

- Athens: A Cultural and Historical Overview by Helena M. Richards – a comprehensive book providing an in-depth look at the history of Athens from its earliest days to the modern era.

- Democracy and Philosophy in Ancient Athens by Nancy R. Felson – an excellent resource for understanding the origins of Western philosophy and its relationship with the political and social framework of ancient Athens.